Many Koreans have big misunderstandings about Islam

This is part of a weekly series of feature stories, videos and podcasts in which The Straits Times correspondents cast the spotlight on people and communities around the region, living in the shadows of their societies where they exist largely unseen, unheard and little talked about.

SEOUL – She hid in a subway station public toilet, seeking refuge from the stares she drew.

It was her first time wearing a hijab, or Islamic headscarf. “Everyone was staring at me, making me feel so shy, so I went to hide and wait for the crowd to disperse,” Ms Song Bo-ra recalled.

Because of a seemingly simple piece of cloth, the South Korean was suddenly a stranger in her home town, the south-eastern port city of Busan.

Ms Song, who is in her 30s, converted to Islam in 2007 after reading about the religion for years. She had been interested in Arabian history and culture since she was young, and found that “Islam is the right religion for me”.

Converting was a deeply personal decision, but wearing the hijab as a symbol of her faith made her stand out from the crowd. She drew stares, even hurtful comments about her religion.

It was only after moving to the capital city Seoul about seven years ago that Ms Song started wearing the headscarf every day.

She lives in Itaewon, known as South Korea’s most multicultural neighbourhood, which is home to the country’s first mosque – Seoul Central Masjid.

Muslims congregate in the precinct every Friday, and before the Covid-19 pandemic, Muslim tourists flocked here for the halal food. Here, she no longer stands out in a hijab.

Even so, she has been bombarded with questions from her countrymen about her choice of headwear.

“Many Koreans have big misunderstandings about Islam. They ask me why I wear the hijab. They think the hijab is used to control women and their freedom, and that we are pressured to wear it,” said the former Islamic teacher who now works at the Korea-Islam Business & Cultural Centre.

She lamented that the hijab is often viewed as a symbol of terrorism, so she gets asked if she supports the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and if she has met ISIS members. “I’d laugh first, then explain that… we want to live peacefully,” she said.

Negative impression continues to persist

In this largely homogeneous country where Buddhism and Christianity are the most dominant religions, Islam is often misunderstood and mistrusted.

Many Koreans associate it with terrorism after the 2007 kidnapping of 23 South Korean missionaries by members of the Taleban. Two were killed before the South Korean government reached a deal for the group’s release.

The saga dominated headlines for weeks, creating a negative impression of Islam that persists till today.

Ms Lee Seul, 32, who is married to a Malaysian, recalled her shock when he told her he was Muslim. They first met at a social gathering in Seoul seven years ago, and he revealed his religion to her only after they became friends.

Her immediate thought, she said, was: “How can this nice and funny guy, who graduated from Korea University and works at Samsung, be a terrorist?”

Confused and in disbelief, she went online for answers. “But all the news, articles and blogs talk only about the bad side of Islam,” she told The Straits Times.

Like most Koreans who use South Korea’s most trusted search engine, Naver, her impressions of the religion and its terrorist links were reinforced in a filter bubble.

She found greater clarity only after searching on Google in English and discussing his religion with him.

Her misconceptions were cleared and the more Ms Lee found out, the more she was drawn to the faith and its way of life. Romance blossomed along the way.

Today, Ms Lee and Mr Muhamad Khalid Ismail, 33, are happily married.

The number of Muslims in South Korea stands at under 200,000 today, just 0.38 per cent of the population, according to an estimate by the Korea Muslim Federation (KMF).

The majority are workers and students from countries such as Turkey, Pakistan and Uzbekistan. About 10,000 of them have acquired Korean citizenship.

Islam was banned in Korea for centuries during the Joseon dynasty (1392-1910) as part of an isolationist policy.

The religion had first been introduced to the Korean peninsula from the 9th to 11th century by Arabians travelling the Silk Road, and revived much more recently by Turkish troops who stayed on after fighting the 1950-53 Korean War.

Some 15,000 Turkish soldiers had volunteered under the United Nations umbrella, and many stayed behind after the war. Some ended up spreading their faith among South Koreans.

KMF deputy director Jang Huseyin said Koreans were touched by the Turkish troops because they valiantly protected them from harm. The soldiers also opened a school for orphaned children and took care of them.

“Turkish soldiers also shared their food because in Islam, we are taught to share food with our neighbours if we know they are hungry,” said Mr Jang, who was born in Turkey but has taken a Korean name as a naturalised citizen.

The 2017 Turkish film Ayla paid tribute to the bond between a Korean child and her Turkish guardian. It is based on the true story of a Turkish soldier who came to South Korea looking for the six-year-old girl placed under his care during the war.

“He had just a photo of her, and he wanted to see her again,” recalled Mr Jang.

A massive search ensued, and their real-life reunion was captured in 2010 by TV station MBC.

“They met in Turkey. It was very emotional. They hugged and cried, and she invited him to Korea,” said Mr Jang. “It was such a lovely story.”

Pushback against ‘Islamisation’

The oil boom in the 1970s saw South Korean firms exporting products and taking on infrastructure projects in the Middle East.

The opening of the Seoul Central Masjid in 1976, thanks in part to donations from Saudi Arabia and Malaysia, also unlocked more opportunities for the nation’s interaction with Islamic countries.

The mosque is one of just 20 mosques in South Korea – a mere fraction of the 77,000 churches.

However, in the past two decades, the government’s attempts to tap the Muslim market were stalled by fierce opposition from the main religious groups.

Restaurant owner Yu Hong-jong recalled how the Lee Myung-bak administration (2008-2013) tried to implement an Islamic finance system in 2012 to bring in money from oil-rich countries, but failed due to fierce opposition from Christian lawmakers.

The next Park Geun-hye administration (2013-2017) tried to turn South Korea into a halal hub to woo Muslim tourists, but also faced stern objection from Christian and Buddhist groups.

“People just didn’t want Islamisation to happen in Korea,” Mr Yu, 62, surmised.

A retired marketeer, he opened South Korea’s first halal-certified Korean restaurant, Eid, in 2014 to cater to Muslim students, workers and tourists who wanted halal Korean food.

Mr Yu had converted to Islam that year, influenced by his eldest son who studied the Arabian language and Islamic finance. His wife and second son are also converts.

They are part of a small and growing group of Korean Muslims, numbering 35,000. As many as 3,000 South Koreans convert to Islam every year, according to the KMF.

But many of them face discrimination and misunderstanding.

“When the Christians came to Korea, they spread their faith through charity work, building schools and hospitals, and grew to become a very powerful force in society. So Korean people think Christians are good people because they did a lot for us,” said Mr Yu.

“But Korean people are biased against Islam because of what they see in the media, like war and instability in Iraq and Afghanistan. Because of that, the first thing Koreans know about Islam is terrorism.”

Cultural exchange

Impressions are hard to change, but recently, Mr Yu has noticed a slight softening in people’s attitudes.

He credits this to the current government’s focus on deepening engagement with South-east Asia.

South Koreans are only now starting to realise that Islam is a way of life, not just in the Middle East but also across South-east Asia, he said. And the region has, for years, been the most popular travel destination for South Koreans.

Meanwhile, the growing popularity of Korean dramas and pop music has started drawing Muslim tourists to Seoul. About one million Muslim tourists visited South Korea in 2019, before the pandemic hit.

Ms Lee and her husband Khalid run a travel company, using their experience to help Muslim tourists navigate around South Korea, and easily find halal food and praying spaces.

They also run YouTube halal travel channel Kimchibudu, which has 47,600 subscribers.

Ms Lee converted to Islam shortly before their wedding in 2017. She said her family was worried that she would have a hard time with religious observances such as praying five times a day, abstaining from pork and alcohol, and fasting during Ramadan, but she had made up her mind to share the same values and lifestyle as her husband.

Given the current travel restrictions due to the pandemic, the couple are now focused on providing halal tourism consulting, such as giving lectures to government officials on how to deal with the needs of Muslim tourists.

“As a local Muslim here, we know how to blend the Korean way with a Muslim lifestyle,” she said, adding that her husband has lived here for 14 years.

Rise of the Korean Muslim influencer

In recent years, young Korean Muslims have taken to social media to share their experiences and raise awareness about Islam.

Among the most successful are Indonesia-based Ayana Moon, who has 3.3 million followers on Instagram, and South Korea-based Daud Kim, who has 2.6 million subscribers on YouTube after gaining fame in Malaysia.

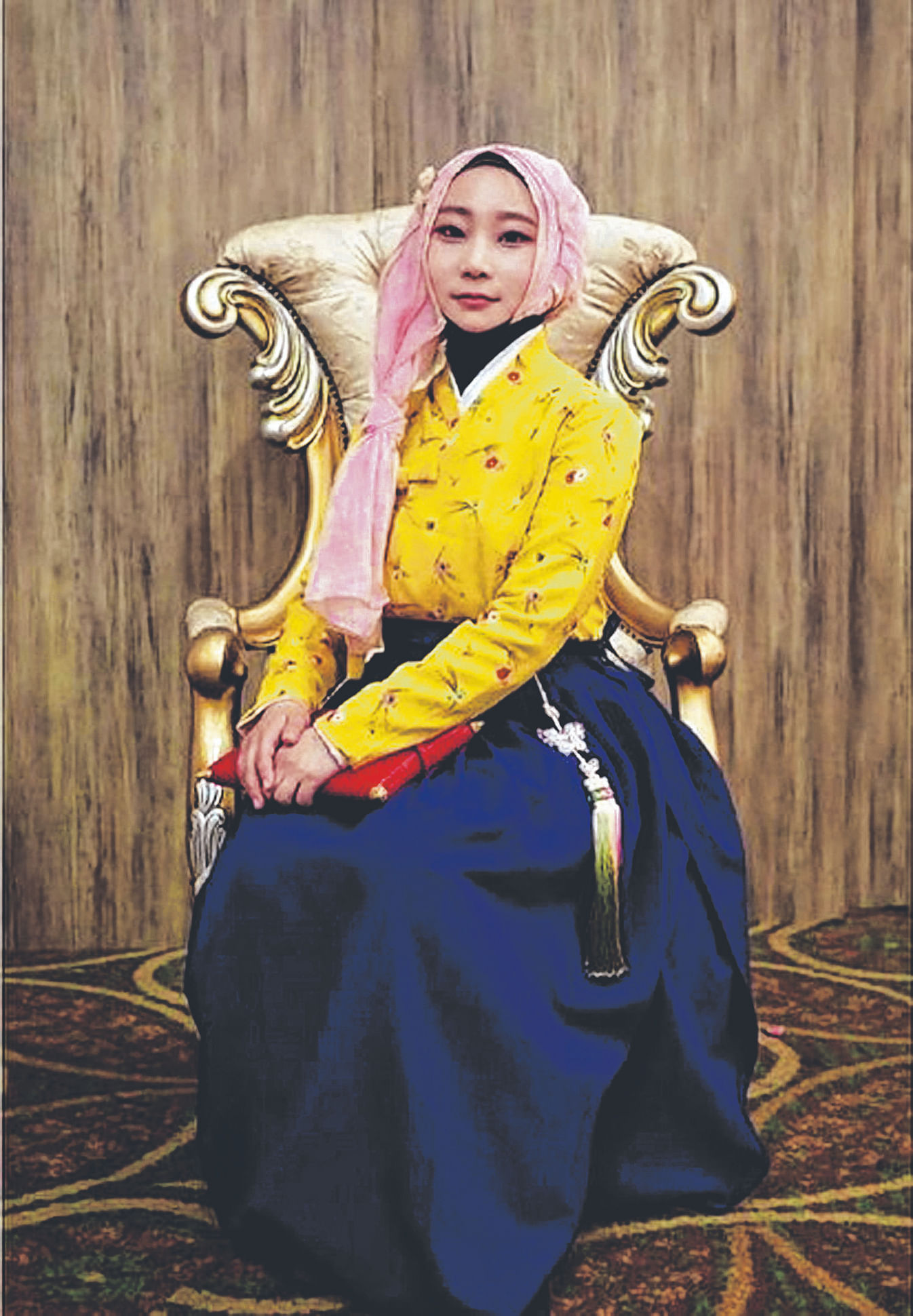

Ms Song, who has 198,000 followers on Instagram, said she uses the channel to promote mutual understanding between Korean Muslims and non-Muslims, as well as to help foreign Muslims understand South Korea better.

She often posts pictures of herself in a hanbok, South Korea’s traditional costume, and finds that it matches well with her hijab.

Despite her good intentions, Ms Song has drawn her fair share of flak. One hater commented, “I’m sure you will wear a bomb jacket one day”.

But she laughed the remarks off, saying “it’s just a misunderstanding”. “I’ll try to explain Islam to them,” she added.

Still, she said she may migrate if she has children in the future, for fear that being born Korean Muslim could set them up for years of being bullied in school.

While it is heartening to see young Korean Muslims online, Mr Jang of KMF said some of them lack in-depth knowledge about Islam and end up sharing misinformation. “I get a little angry because some of them are just using Islam to make money,” he added.

Mr Kim, for one, was accused of converting to Islam to profit from it. He was also embroiled in a sexual assault case last year, though he later claimed he was set up.

Ms Lee is also worried that the extreme antics of some Korean Muslim YouTubers, such as praying in the middle of the road, may turn people off.

While this might earn them kudos for their piety among some Muslims abroad, it only feeds the suspicions of those Koreans with jaundiced views towards Islam, she said.

While she is happy to embrace Islam, Ms Lee is not ready yet to don the hijab every day.

“I will wear the hijab in Malaysia because no one will disturb me,” she said. “But in Korea, people might attack me. They might pull my hijab off, tell me I’m crazy, scold me, swear at me, or say things like ‘Just be a normal Korean if you are Korean’. I’m not ready for that, I’m not so brave.

“So if I need to wear the hijab out, I’d speak English only so Korean people think I’m a foreigner. It’s easier that way.”

Number of View :1010