Reply To Robert Morey’s Moon-God Allah Myth: A Look At The Archaeological Evidence

Reply To Robert Morey’s Moon-God Allah Myth: A Look At The Archaeological Evidence

M S M Saifullah, Mohd Elfie Nieshaem Juferi & ‘Abdullah David

© Islamic Awareness, All Rights Reserved.

First Composed: 13th April 2006

Last Modified: 15th September 2007

And from among His Signs are the night and the day, and the sun and the moon. Prostrate not to the sun nor to the moon, but prostrate to Allah Who created them, if you (really) worship Him. (Qur’an 41:37)

One of the favourite arguments of the Christian missionaries over many years had been that Allah of the Qur’an was in fact a pagan Arab “Moon-god” from pre-Islamic times. The seeds of this argument were sown by the work of the Danish scholar Ditlef Nielsen, who divided the Semitic deities into a triad of Father-Moon, Mother-Sun and Son-Venus.[1] His ideas (esp., triadic hypothesis) were used uncritically by later scholars who came to excavate many sites in the Near East and consequently assigned astral significance to the deities that they had found. Since 1991 Ditlef Nielsen’s views were given a new and unexpected twist by the Christian polemicist Robert Morey. In a series of pamphlets, books and radio programs, he claimed that “Allah” of the Qur’an was nothing but the pagan Arab “Moon-god”. To support his views, he presented evidences from the Near East which can be seen in “Appendix C: The Moon God and Archeology” from his book The Islamic Invasion: Confronting The World’s Fastest-Growing Religion and it was subsequently reprinted with minor changes as a booklet called The Moon-God Allah In The Archeology Of The Middle East.[2] It can justifiably be said that this book lies at the heart of missionary propaganda against Islam today. The popularity of Morey’s ideas was given a new breath of life by another Christian polemicist Jack T. Chick, who drew a fictionalised racially stereotyped story entitled “Allah Had No Son”.

Morey’s ideas have gained widespread popularity among amenable Christians, and, more often than not, Muslims find themselves challenged to refute the ‘archaeological’ evidence presented by Morey. Surprisingly, it has also been suggested by some Christians that Morey has conducted “groundbreaking research on the pre-Islamic origins of Islam.” In this article, we would like to examine the two most prominent evidences postulated by Morey, namely the archaeological site in Hazor, Palestine and the Arabian “Moon temple” at Hureidha in Hadhramaut, Yemen, along with the diagrams presented in Appendix C of his book The Islamic Invasion: Confronting The World’s Fastest-Growing Religion (and booklet The Moon-God Allah In The Archeology Of The Middle East) all of which he uses to claim that Allah of the Qur’an was a pagan “Moon-god”.[3]

2. The Statue At Hazor: “Allah” Of The Muslims?

One of the most prominent evidences of Morey for showing that Allah was a “Moon god” comes from Hazor.[4] Morey says:

In the 1950’s a major temple to the Moon-god was excavated at Hazor in Palestine. Two idols of the moon god were found. Each was a stature of a man sitting upon a throne with a crescent moon carved on his chest (see Diagram 1). The accompanying inscriptions make it clear that these were idols of the Moon-god (see Diagram 2 and 3). Several smaller statues were also found which were identified by their inscriptions as the “daughters” of the Moon-god.[5]

Hazor was a large Canaanite and Israelite city in Upper Galilee. It was identified by J. L. Porter in 1875 and this view was later endorsed by J. Garstang who conducted trials at the site in 1928. In the years 1955-58, the James A. de Rothschild Expedition, under the direction of Yigael Yadin, conducted excavations on the site.[6] Among other things, they found a shrine furnished with an offering table, a lion orthostat, the statue in question, and stelae, all made from regional black basalt [Figure 1(a)].[7] The central stela shows a pair of hands raised below a crescent plus circle symbol, usually considered to depict the crescent moon and the full moon, respectively [Figure 1(b)]. The raised hands may be understood as a gesture of supplication, although Yadin proposed that this posture should be associated with a goddess known from much later Punic iconography as Tanit, who was the consort of the god Sin.[8] The other stelae are plain. The whole shrine has been interpreted as belonging to a Moon-god cult.

|

|

|

(a) |

(b) |

Figure 1: (a) A close-up of the stelae temple, showing all the stelae, the statue and the offering table. (b) The central stele with the relief.[9]

Figure 2: (Right) Front view of the statue, showing the lunar deity emblem on its chest. (Left) Rear view of the statue.[10]

The principal object of interest is the statue [Figure 2] which Morey has labelled as a “Moon-god”.[11] The statue, about 40 cm in height, depicts a man with an inverted crescent suspended from his necklace and holding a cup-like object in his right hand, while the other hand rests on his knees.[12] The question now is what exactly this statue represents which Morey labelled as “Moon-god”?

According to Yadin, this statue can represent a deity, a king, or a priest. He says that all the “three alternatives are possible”, but he “believes it is a statue of the deity itself”.[13] However, it appears that later he had modified his views. Writing in the Encyclopedia Of Archaeological Excavations In The Holy Land, Yadin describes the same statue as

Basalt statue of deity or king from the stelae temple…[14]

Subsequent scholarship has described the same statue either in uncertain or neutral terms. For example, Treasures Of The Holy Land: Ancient Art From The Israel Museum describes the statue of the seated figure as:

It depicts a man, possibly a priest, seated on a cubelike stool. He is beardless with a shaven head; his skirt ends below his knees in an accentuated hen; his feet are bare. He holds a cup in his right hand, while his left hand, clenched into a fist, rests on his left knee. An inverted crescent is suspended from his necklace.[15]

Amnon Ben-Tor in The New Encyclopedia Of Archaeological Excavations In The Holy Land describes the statue as a “seated male figure” without saying what it represented.[16] In a later publication, however, he described the same object as “a small basalt statue of a decapitated deity (or king) whose head was found nearby.”[17] Amihai Mazar, in a similar fashion, described the statue as “a sitting male figure (possibly depicting a god or a priest).”[18]

Clearly, there is a difference of opinion among the scholars concerning this statue. It is not too hard to understand why this is the case. It seems illogical that a god should hold offering vessels in his hand; the god is usually the one who receives offerings. Therefore, the statue should, in all probability, depict a priest or a worshipper of a god, who himself is in a way considered present, either invisibly or in the upright stela of the sanctuary. Furthermore, the statue of a man holding an offering was seated at the left hand side of the shrine [Figure 1(a)]. This can hardly be a proper position for a revered god, whose position is arranged in the centre of the sanctuary.

Morey claimed that “two idols of the Moon-god were found” and that each of them were “sitting upon a throne with a crescent moon carved on his chest”. Apparently, the “accompanying inscriptions made it clear that these were idols of the Moon-god”. Regardless of the difference of opinions concerning the nature of statue found at Hazor no scholar has ever identified this statue with a “Moon-god”, nor do they say that “accompanying inscriptions” suggest that the statue was that of a “Moon-god”. Furthermore, Morey claimed that “two idols of the Moon-god” were found at Hazor. Contrary to his claims of the discovery of “two idols of the Moon-god”, Yadin confirms the discovery of two contemporary temples, dedicated to two different deities – Moon-god and Weather god at Hazor in Area C and Area H, respectively.[19] The temple of the Weather god was represented by a circle-and-rays emblem and the bull which together indicate that it must be Hadad the storm god,[20] whatever his actual name was at Hazor. A likely source of Morey’s unsubstantiated claims could be due to the discovery of two beheaded statues, one with an inverted crescent suspended from his necklace that we had discussed earlier and the other representing a king;[21] they look similar to each other. Equally ridiculous is another of Morey’s claims that several smaller statues were also found “which were identified by their inscriptions as the “daughters” of the Moon-god.” No such statues or inscriptions accompanying them were found in Hazor. Unfortunately for Morey he has been caught red-handed fabricating evidence. Put simply, he is making up stories here.

After Morey’s debacle at Hazor, let us now examine his next piece of evidence – that of a “Moon temple” at Hureidha in Southern Arabia and how it proves that Allah of the Qur’an was a pagan “Moon-god” of Arabia.

3. The “Moon” Deities From Southern Arabia?

Morey’s claim that the moon worship was dominant in Arabia, especially in the south, can be summed up with a quote from his book:

During the nineteenth century, Amaud, Halevy and Glaser went to Southern Arabia and dug up thousands of Sabean, Minaean, and Qatabanian inscriptions which were subsequently translated. In the 1940’s, the archeologists G. Caton Thompson and Carleton S. Coon made some amazing discoveries in Arabia. During the 1950’s, Wendell Phillips, W.F. Albright, Richard Bower and others excavated sites at Qataban, Timna, and Marib (the ancient capital of Sheba)…

The archeological evidence demonstrates that the dominant religion of Arabia was the cult of the Moon-god…

In 1944, G. Caton Thompson revealed in her book, The Tombs and Moon Temple of Hureidha, that she had uncovered a temple of the Moon-god in southern Arabia. The symbols of the crescent moon and no less than twenty-one inscriptions with the name Sin were found in this temple. An idol which may be the Moon-god himself was also discovered. This was later confirmed by other well-known archeologists.[22]

Let us now look into the so-called “amazing discoveries” made in Southern Arabia which led Morey to claim that the archaeological evidence “demonstrates” that the dominant religion in Arabia was the cult of a Moon-god.

To begin with, the South-Arabian pantheon is not properly known. Its astral foundation is indisputable. As in most contemporary Semitic cults, the southern Arabs worshipped stars and planets, chief among whom were the Sun, Moon and ‘Athtar, the Venus.[23] The relation to the divine was deeply rooted in public and private life. The concept of State was expressed through the “national god, sovereign, people”. Each of the South Arabian kingdoms had its own national god, who was the patron of the principal temple in the capital. In Sheba, it was Ilmaqah (also called Ilumquh or Ilmuqah or Almaqah or Almouqah), in the temple of the federation of the Sabaean tribes in Marib. In Hadramaut (or Hadhramaut), Syn (or Sayin) was the national god and his temple was located in the capital Shabwa. In Qataban, the national god was called ‘Amm (“paternal uncle”), who was the patron of the principal temple in the capital Timna‘. ‘Amm was seen as a protector of the Qatabanite dynasty, and it was under his authority that the ruler carried out various projects of the state. In Ma‘in, the national god was Wadd (“love”) and it originated most probably from Northern Arabia. He was sometimes invoked as Wadd-Abb (“Wadd is father”).[24]

In order to understand the religion and culture of Southern Arabia, it must be borne in mind that the monuments and inscriptions already show a highly developed civilization, whose earlier and more primitive phases we know nothing about. This civilization had links with the Mediterranean region and Mesopotamian areas – which is evidenced by the development and evolutionary trends of its architecture and numismatics. This exchange certainly influenced the religious phenomena of the culture and it is primarily here we should look to illuminate the theological outlook of the Sheba region; certainly not among the nomadic bedouin of the centre and north of the Arabian peninsula. It was the failure to take into account these crucial principles that led Ditlef Nielsen into his extravagant hypothesis that all ancient Arabian religion was a primitive religion of nomads, whose objects of worship were exclusively a triad of the Father-Moon, Mother-Sun and the Son-Venus star envisaged as their child.[25] Not only was this an over-simplified view based on an unproven hypothesis, it is also quite absurd to think that over a millennium-long period during which paganism is known to have flourished, there was not substantial shifts of thinking about the deities. Not surprisingly, Nielsen’s triadic hypothesis was handed a devastating refutation by many scholars (a detailed discussion is available below), albeit some of them still retained his arbitrary assignment of astral significance to the deities.[26] While discussing the pantheon of South Arabian gods and its reduction to a triad by Nielsen, Jacques Ryckmans says:

Many mention of gods are pure appellations, which do not allow defining the nature, or even the sex, of the deities names. This explains why the ancient claim of D. Nielsen to reduce the whole pantheon to a basic triad Moon-father, Sun-mother (sun is feminine in Arabia), and Venus-son, has continued to exert negative influence, in spite of its having been widely contested: it remained tempting to explain an unidentified feminine epithet as relating to the Sun-goddess, etc.[27]

The crude logic of the proponents of Nielsen’s hypothesis is that since Shams (“Sun”) is feminine in epigraphic South Arabian, the other principal deity must be masculine and this was equated with the moon. The relationship between Father-Moon and Mother-Sun produced Son-Venus star, their child. How did this erroneous interpretation affect the data from Southern Arabia where some “amazing discoveries” were made? We will examine this is the next few sections.

Nielsen’s views also influenced the archaeologists who excavated the Mahram Bilqis (also known as the Temple Awwam) near Marib.[28] Mahram Bilqis, an oval-shaped temple, was dedicated to Ilmaqah, the chief god of Sheba.[29] This temple was excavated by the American Foundation for the Study of Man (AFSM) in 1951-52[30] and again more recently in 1998.[31] According to the archaeologist Frank Albright, the Temple Awwam (i.e., Mahram Bilqis) was “dedicated to the moon god Ilumquh, as the large inscription of the temple itself tells us”.[32] Albright cited the inscription MaMB 12 (= Ja 557) to support his claim that Temple Awwam was “dedicated to the moon god Ilumquh”.[33] However, the inscription Ja 557 in its entirety reads:

Abkarib, son of Nabatkarib, of [the family] Zaltān, servant of Yada‘il Bayyin and of Sumhu‘alay Yanūf and of Yata‘amar Watar and of Yakrubmalik Darih and of Sumuhu‘alay Yanūf, has dedicated to Ilumquh all his children and his slaves and has built and completed the mass of the bastion [by which] he has completed and filled up the enclosing wall of Awwām from the line of this inscription and in addition, all its masonry of hewn stones and its woodwork and the two towers Yazil and Dara‘ and their [the two towers] recesses, to the top, and he has raised up the possessions of his ancestors, the descendents of Zaltān. By ‘Attar and by Ilumquh and by Dāt Himyān and by Dāt Ba‘dān. And Abkarib has made known, in submission to Ilumquh and to the king of Mārib, Š[…[34]

Although the dedication to Ilmaqah is mentioned, nowhere does the inscription say that Ilmaqah is called the Moon-god! In fact, none of the inscriptions at the Mahram Bilqis mention Ilmaqah as the Moon-god. Moreover, the collective mentioning of the pantheon of gods by formulae such as “by ‘Athtar”, “by Ilumquh”, “by Shams”, “by Hawbas”, “by Dhāt Himyān”, “by Dhāt Ba‘dān”, “by Dhāt Ba‘dānum”, “by Dhāt Zahrān”, etc. occur quite frequently in the inscriptions from Mahram Bilqis.[35] As Ryckmans had pointed out, many of these gods are pure appellations, with no defining nature and sex. Following the logic of Nielsen of reducing the Arab pantheon of gods to a triad, Albright and others have considered Ilmaqah as the Moon-god, although no evidence of such a triad exists. Scholars like Alexander Sima have drawn attention to the fact that very little is known about the Sabaean deities. He says that while Shams was most certainly a solar goddess, the lunar nature of Ilmaqah is “speculative” and lacks “any epigraphic evidence”.[36]

The nature of the Sabaean chief deity Ilmaqah was studied in considerable detail by J. Pirenne[37] and G. Garbini[38] in the 1970s. They have shown that the motifs associated with Ilmaqah such as the bull’s head, the vine, and also the lion’s skin on a human statue are solar and dionysiac attributes. Therefore, Ilmaqah was a Sun-god, rather than a Moon-god. Concerning Ilmaqah, J. Ryckmans in The Anchor Bible Dictionary says:

Along with the main god ‘Attar, each of the major kingdoms venerated its own national god. In Saba this was the god named Almaqah (or Ilmuqah), whose principal temple was near Marib, the capital of Saba, a federal shrine of the Sabaean tribes. According to the widely contested old theory of the Danish scholar D. Nielsen, who reduced the whole South Arabian pantheon to a primitive triad: father Moon, mother Sun (sun is feminine in Arabic) and son Venus, Almaqah was until recently considered a moon god, but Garbini and Pirenne have shown that the bull’s head and the vine motif associated with him are solar and dionysiac attributes. He was therefore a sun god, the male counterpart of the sun goddess Šams, who was also venerated in Saba, but as a tutelary goddess of the royal dynasty.[39]

Ilmaqah was also discussed by A. F. L. Beeston. Writing in the Encyclopaedia Of Islam, he says:

For the period down to the early 4th century A.D., few would now agree with the excessive reductionism of D. Nielsen, who in the 1920s held that all the many deities in the pagan pantheon were nothing more than varying manifestations of an astral triad of sun, moon and Venus-star; yet it is certainly the case that three deities tend to receive more frequent mention than the rest….

But just as the Greek local patron deities such as Athene in Athens, Artemis in Ephesus, etc., figure more prominently than the remoter and universal Zeus, so in South Arabia the most commonly invoked deity was a national one, who incorporated the sense of national identity. For the Sabaeans this was ‘lmkh (with an occasional variant spelling ‘lmkhw). A probable analysis of this name is as a compound of the old Semitic word ‘l “god” and a derivative of the root khw meaning something like “fertility” (cf. Arabic kahā “flourish”); the h is certainly a root letter, and not, as some mediaeval writers seem to have imagined, a tā marbūta, which in South Arabian is always spelt with t…

Many European scholars still refer to this deity in a simplistic way as “the moon god”, a notion stemming from the “triadic” hypothesis mentioned above; yet Garbini has produced cogent arguments to show that the attributes of ‘lmkh are rather those of a warrior-deity like Greek Herakles or a vegetation god like Dionysus.[40]

Elsewhere, Beeston writes:

In the case of Ilmqh, ‘Amm and Wadd, there is nothing to indicate lunar qualities. Garbini has presented a devastating critique of such a view in relation to Ilmqh, for whom he claims (much more plausibly) the attributes of a warrior-god and of a Dionysiac vegetation deity, with solar rather than lunar associations. In the case of Wadd, the presence of an altar to him on Apollo’s island of Delos points rather to solar than lunar associations. For ‘Amm we have nothing to guide us except his epithets, the interpretation of which is bound to be highly speculative.[41]

While discussing various gods of southern Arabia, and Ilmaqah (or Almaqah) in particular, Jean-François Breton says:

Almaqah was the god of agriculture and irrigation, probably for the most part of the artificial irrigation which was the basis of successful farming in the oasis of Ma’rib. The god’s animal attributes were the bull and, in later times, the vine. Almaqah was a masculine sun god; the divinity Shams (Sun), who was invoked as protector of the Sabaean dynasty, was his feminine counterpart.[42]

Such views concerning Ilmaqah can also be seen in the Encyclopaedia Britannica which says:

Next to ‘Athtar, who was worshiped throughout South Arabia, each kingdom had its own national god, of whom the nation called itself the “progeny” (wld). In Saba’ the national god was Almaqah (or Ilmuqah), a protector of artificial irrigation, lord of the temple of the Sabaean federation of tribes, near the capital Ma’rib. Until recently Almaqah was considered to be a moon god, under the influence of a now generally rejected conception of a South Arabian pantheon consisting of an exclusive triad: Father Moon, Mother Sun (the word “sun” is feminine in Arabic), and Son Venus. Recent studies underline that the symbols of the bull’s head and the vine motif that are associated with him are solar and Dionysiac attributes and are more consistent with a sun god, a male consort of the sun goddess.[43]

While discussing the relationship between the Chaldaeans and the Sabianism, the Encyclopedia Of Astrology says:

From this arose Sabianism, the worship of the host of heaven: Sun, Moon and Stars. It originated with the Arabian kingdom of Saba (Sheba), when came the Queen of Sheba. The chief object of their worship was the Sun, Belus. To him was erected the tower of Belus, and the image of Belus.[44]

It is clear from this discussion that Ilmaqah was the patron deity of the people of Sheba due to the fact they invoke him frequently in their inscriptions, and almost always before other deities if at all featured. From the inscriptions themselves it is not clear what sort of deity Ilmaqah was. He has many epithets, but none which link him explicitly with the sun or moon. The simple linkages between deities and natural phenomena as put forth by Nielsen have been rejected of late in explaining the nature and function of deities. Instead, the study of the motifs show that Ilmaqah had attributes that are more consistent with a Sun-god.[45]

MOON GOD IN HUREIDHA (HADRAMAUT)?

Let us now move to Hadramaut. During excavations in Southern Arabia, G. Caton Thompson found a temple of the Hadramitic patron deity Sin in Hureidha.[46] She claimed that Sin was a Moon-god.[47] Following her footsteps, Morey says:

In 1944, G. Caton Thompson revealed in her book, The Tombs and Moon Temple of Hureidha, that she had uncovered a temple of the Moon-god in southern Arabia (see Map 3). The symbols of the crescent moon and no less than twenty-one inscriptions with the name Sin were found in this temple (see Diagram 5). An idol which may be the Moon-god himself was also discovered (see Diagram 6). This was later confirmed by other well-known archeologists.[48]

There are several serious problems associated with G. Caton Thompson’s claim that Sin was a Moon-god. Firstly, the name of the Hadramitic patron deity according to the epigraphic evidence is ![]() and it is transcribed as SYN.[49] The case for SYN being a Moon-god rests on identifying him with the Akkadian Su-en, later Sin: the well-known north Semitic moon deity. The presence of three consonants in the name of the Hadramitic deity SYN poses problems for one wishing to equate it with the Babylonian deity Sin which is written by two signs to be pronounced EN-ZU (or ZU-EN). This problem was recognized by Albright over 50 years ago. Although he alleges that SYN was borrowed from an unknown Akkadian form of Sumerian Zuen, he did not know how and was therefore at loss to explain how this process would have occurred.

and it is transcribed as SYN.[49] The case for SYN being a Moon-god rests on identifying him with the Akkadian Su-en, later Sin: the well-known north Semitic moon deity. The presence of three consonants in the name of the Hadramitic deity SYN poses problems for one wishing to equate it with the Babylonian deity Sin which is written by two signs to be pronounced EN-ZU (or ZU-EN). This problem was recognized by Albright over 50 years ago. Although he alleges that SYN was borrowed from an unknown Akkadian form of Sumerian Zuen, he did not know how and was therefore at loss to explain how this process would have occurred.

The original uncontracted Accadian form of Sumerian Zuen is not known, but may have been *Zuyen > *Ziyen, from which the Hadrami name of the moon god, SYN, was borrowed at a very early date – how is unknown. It should be noted that the Sumerian z is regularly reflected by Accadian s in borrowed words, and that the Hadrami word cannot be transcribed Sîn, as customarily done, but had three consonants.[50]

Clearly, if the spelling difference between the Babylonian Sin and the Hadramitic SYN was “remarkably close”, as the missionaries have claimed, why is it that prominent scholars such as W. F. Albright deny the transcription of SYN to Sin and resorted to speculation? It is clear that equating SYN with Babylonian Sin is fraught with problems, and as Beeston had correctly noted:

Among the federal deities, the case for Syn being a moon god rests on identifying him with Akkadian Su-en, later Sin; an equation which, attractive though it may seem, is not without problems. At all events, even if this was so with the Hadramite deity, it is unlikely that it tells the whole story.[51]

Furthermore, he points out the geographical difficulty in accepting the equation of Sayīn being the equivalent of the Mesopotamian Sin:

On the east coast of Arabia, where Mesopotamian influence would be expected to be greater than in Hadramawt, we find mention of a deity with a similar name but spelt with a different initial consonant.[52]

Secondly, Pliny reported that in Shabwa, they worshipped the god Sabin.[53] Sabin was pronounced as Savin according to the Latin phonetic rules of the 1st century CE.[54] As mentioned earlier, the Hadramitic patron deity is transcribed as SYN and it is a three consonant word. As for the nature of the vowels between the consonants, Pliny gives a clue that in Shabwa, people worshipped the god Sabin. If we remove the consonants in Pliny’s description of the Hadramitic deity and insert the consonantal structure from epigraphic South Arabian, we are left with the nearest and perhaps most accurate pronunciation of SYN as Sayīn. Christian Robin proposed the reading of Sayīn for SYN which is now widely accepted among scholars.[55] Commenting on the Hadramitic patron god SYN, Alexander Sima says:

The Hadramitic pantheon is the least known in southern Arabia owing to the fact that the number of known Hadramitic inscriptions is – compared to the three other states/languages – still very limited. At the top of the Hadramitic pantheon stood the deity whose name was constantly written SYN. This name was previously thought to be vocalized as Sīn and thus connected with the well-known north Semitic moon deity, Sīn. However, the South Arabian orthography and the testimony of the Natural History of Pliny the Younger points to a vocalization, Sayīn, so the form Sīn should be abandoned. The Hadramitic sources give no hint of his nature and even his connection with the moon is merely speculative.[56]

In other words, the Hadramitic patron deity Sayīn is different from the north Semitic deity Sin. Consequently, the former’s connection with the moon is speculative.

(a)

(b)

Figure 3: (a) Couple of Hadramitic coins mentioning the patron deity SYN (obverse) and showing an eagle with open wings (Reverse).[57] (b) The coin 1 is sketched to make the depiction more lucid.[58]

However, the numismatic evidence from Hadramaut suggests something more interesting (See the appendix On The “Moon-God” Coins Of Ancient Southern Arabia for a detailed discussion). In some coins from Hadramaut, Sayīn appears as an eagle [Figure 3(a)],[59] a solar animal, and this clearly points to him as being the Sun-god. John Walker, who first published the Hadramitic coins, was perplexed by the presence of an eagle and the mention of SYN, which he assumed to be the deity Sin. Although he was aware that the monuments in North Arabia and Syria regarded the eagle as a solar deity, he insisted on giving a lunar association to the depiction of eagle on Hadramitic coins, which is clearly in contrary to the evidence.[60] Modern scholars regard Sayīn as a solar deity. For example, Jean-François Breton says:

The national god of Hadramawt was known as Sayîn, a Sun god. As in Qataban, the inhabitants of Hadramawt referred to themselves as the “children of Sayîn”; the state itself was described through the formula using two divine names which also referred to a double tribe: “Sayîn and Hawl and [king] Yada’il and Hadramawt.” We have only meagre information from classical authors about Sayîn and his cult. Theophrastus reported that frankincense was collected in the temple of the Sun, which he erroneously placed in Saba.[61]

Similarly Jacques Ryckmans points out:

In Hadramawt, the national god Syn, in the temple in the capital Shabwah, has generally been assimilated to the Moon-god. But remarks by Theophrastes and Pliny, and some coins on which he appears as an eagle (a solar animal!) point him out as a Sun-god, a male counterpart of Shams.[62]

Such views are also seen in The Anchor Bible Dictionary[63] and the Merriam-Webster’s Encyclopedia Of World Religions. The latter says:

In Hadramawt the national god Syn was also a sun god.[64]

Given that Morey claims to have conducted “groundbreaking research on the pre-Islamic origins of Islam”, one finds oneself most taken aback by the complete absence of contemporary scholarship in his book. Morey’s haphazard consideration of the sources would justifiably prompt one to fear that he was not even aware of the relevant critical literature in the first place! All this leaves the apologist’s credibility in serious dispute.

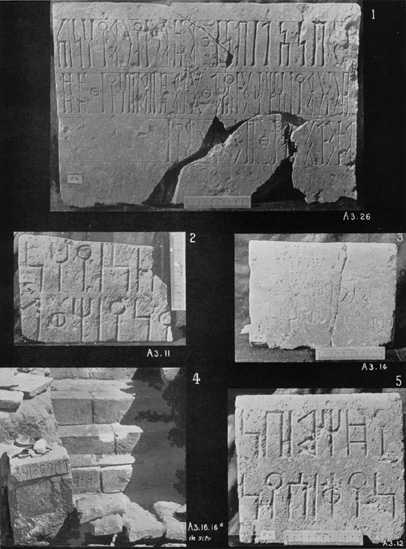

Let us now look at his arguments concerning the “Moon temple” in Hureidha. Morey says that “symbols of the crescent moon and no less than twenty-one inscriptions with the name Sin were found in this temple (see Diagram 5).” The presence of crescent moon does not automatically suggest that Sayīn was a Moon-god. Müller had photographed an incense altar from Southern Arabia containing both crescent moon and the sun. This object was dedicated to the Sun-goddess.[65] Clearly the presence of a crescent moon does not warrant drawing hasty conclusions. Moreover, Morey pointed to the diagram 5 containing the inscriptions to support his viewpoint. This diagram is reproduced with a translation in Figure 4.

(a)

|

A3.26

|

|

|

A3.11

|

A3.14

|

|

A3.16

A3.16a

|

A3.12

|

(b)

Figure 4: (a) Inscriptions at Temple in Hureidha dedicated to the patron deity Sayīn or SYN. (b). Translation of the inscriptions.[66]

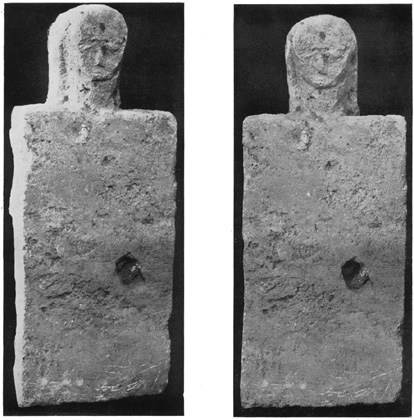

Out of six inscriptions, only one mentions the dedication of the temple at Hureidha to Sayīn. In fact, none of the dedicatory inscriptions (or otherwise) say that Sayīn was a Moon-god.[67] Morey goes on to claim with a picture (i.e., Diagram 6 in his book and see Figure 5 below) that G. Caton Thompson discovered an “idol which may be the Moon-god himself”. This uncertainty is mysteriously transformed to certainty by Morey in the figure caption which reads “Arabian Moon Temple – An idol of the Moon-god”.[68] There is a clear discrepancy here.

Figure 5: Limestone statue of unknown significance.[69]

Moreover, what does G. Caton Thompson say about this image? Her description of this statue is as follows:

White limestone brick with impurities. Total height 20.5 cm., width 8.4 cm., depth 4 cm. Head and neck 5.5 cm. high. The brick belongs to a class of smooth chiselled slabs abundant in the Temple masonry… The back of the image, however, though rough to stand hidden against a wall, is not humped for actual engagement. The human features, without ears, are vaguely indicated on a bullet head; and hair, or a hanging head-dress, not infrequent on Yemen statuettes, falls to the shoulders.

Neither of these stones has any near parallel in published material from south Arabia. They are, in their respective ways, more primitive than anything yet found there. The significance of association of the true baetyl – the aniconic representation of the god – with the semi-anthromorphic form of image, more probably representative of the votary, in a similar ritual setting, is perhaps impossible to disentangle without additional evidence from comparable groups in situ.[70]

In the layman terms, the exact nature of this limestone statue is not known although Thompson suggests that “it may be a cult image.”[71] Morey’s claim that Figure 5 represents the “idol of the Moon-god” is now completely sunk. What now becomes unbelievable is what comes next. Morey says that the limestone statue of the non-existing Moon-god at Hureidha “was later confirmed by other well-known archeologists”. The well-known archaeologists that are listed by Morey are:

Richard Le Baron Bower Jr. and Frank P. Albright, Archaeological Discoveries in South Arabia, Baltimore, John Hopkins University Press, 1958, p.78ff; Ray Cleveland, An Ancient South Arabian Necropolis, Baltimore, John Hopkins University Press, 1965; Nelson Gleuck, Deities and Dolphins, New York, Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 1965).[72]

Three references are listed but only one is cited with a page number. Page number 78ff. in Archaeological Discoveries In Southern Arabia leads to the article “Irrigation In Ancient Qatabān (Beihān)” by Richard LeBaron Bowen, Jr.[73] On p. 78, Bowen says:

We are indebted to Misses F. Stark, E. W. Gardner, and G. Caton Thompson for the first systematic study of ancient irrigation in South Arabia. Freya Stark visited Hureidha in 1935 and reported that a very big Sabaean ruin-field existed in Wadi ‘Amd, a tributary of Wadi Hadhramaut (Plate 34). On the basis of this, Miss Caton Thompson chose Hureidha as a site for excavation in 1937. The “Sabaean ruin-field” turned out to be merely the rubble ruins of an irrigation system, which Miss E. W. Gardner surveyed (Plate 90).[74]

In the footnote of the page Bowen cites G. Caton Thompson’s The Tombs And Moon Temple Of Hureidha (Hadhramaut) where the ruins of the irrigation system are discussed. This does not sound like well-known archaeologists “confirming” the limestone statue as “Moon-god”.

Morey’s deception gets grander with the next reference he cited, which is Ray Cleveland’s An Ancient South Arabian Necropolis. The full title of this book reads An Ancient South Arabian Necropolis: Objects From The Second Campaign (1951) In The Timna‘ Cemetery.[75] The last part of the title of the book which Morey conveniently left-out is more informative. Timna‘ is in Qataban whereas Hureidha is in Hadramaut. Cleveland’s book exclusively deals with Timna‘’s cemetery in Qataban and as to how he had confirmed that the limestone statue at Hureidha in Hadramaut was a “Moon-god” is a complete mystery. The fact is that there is no such “confirmation” by Cleveland in his book. No wonder Morey did not even cite a page number in his book where the reader can verify his claims.

Morey’s deception peaks with the last reference on the list, i.e., Nelson Gleuck’s Deities And Dolphins. The full title of this book is Deities And Dolphins: The Story Of The Nabataeans.[76] Again the last part of the title gives the whole game away and no wonder Morey did not mention it at all. In this book Glueck describes the Nabataean hilltop temple of Khirbet Tannur.[77] Khirbet Tannur is about fifty miles north of Petra, on the peak of Jebel Tannur in modern day Jordan. Not surprisingly, this book has nothing to do with the temple in Hureidha in Southern Arabia and it does not even mention it. Consequently, there is no “confirmation” by Glueck that the statue at Hureidha was a “Moon-god”.

This completely refutes the “archaeological evidence” presented by Morey for his claim that “Allah” of the Qur’an was in fact a pagan Arab “Moon-god” of pre-Islamic times. To complete the study of the pantheon in Southern Arabia in pre-Islamic times, let us look at the nature of ‘Amm, the patron of the principal temple in the capital Timna‘ in Qataban and Wadd, the national god of Ma‘in.

MOON GODS IN QATABAN AND MA‘IN?

The astral nature of the patron deities of Qataban and Ma‘in is uncertain. Ryckmans says in The Anchor Bible Dictionary:

In Ma‘in, the national god Wadd, “love” originated from North Arabia… is frequently associated with the symbol of the moon crescent and a small disc (the planet Venus?), so that he probably was a moon god… In Qataban, the national god was ‘Amm, “paternal uncle,” a well known semitic divine name. There is no reason to consider him moon god.[78]

Elsewhere he states:

In Ma‘in the national god Wadd, “love” originated from North Arabia. The identification with the Moon-god is not established… In Qatabān, the national god was called ‘Amm, “paternal uncle”. His identity with the Moon-god is not established.[79]

Ryckmans’ views are also shared by Breton. He says that:

In the kingdom of Ma‘in, the national god was known as Wadd, or “love”; this god probably originated in central or northern Arabia and has been attested in several kingdoms in South Arabia. He is a lunar god whose name is sometimes accompanied by the epithet moon…

In Qatabān, the national god was called ‘Amm or “paternal uncle” in reference to his role in the pantheon; but this designation fails to reveal his full identity.[80]

However, Beeston disagrees with the view that Wadd can be considered as a Moon-god. He opines that Wadd is most likely a solar deity. As for ‘Amm he says that there is nothing certain about his astral character. Beeston says:

In the case of Wadd, the presence of an altar to him on Apollo’s island of Delos points rather to solar than lunar associations. For ‘Amm we have nothing to guide us except his epithets, the interpretation of which is bound to be highly speculative…[81]

In summary, the scholars are divided over the astral nature of both Wadd, the patron deity of Ma‘in, and ‘Amm, the patron of the principal temple in the capital Timna‘. However, there is complete agreement concerning ‘Amm, the patron deity of Qataban, that his exact nature is unknown.

DITLEF NIELSEN, YAHWEH’S “MOONOTHEISM” AND THE INCORRIGIBLE MISSIONARIES

Given the fact that the modern scholarship categorically rejects or cast doubts on the lunar association of the ancient South Arabian deities, the missionaries now turn to a very familiar pattern of name calling using emotionally-laden terms such as “liberal” scholarship, “secular” scholarship and in the current case “revisionist” scholarship, to uncritically dismiss the arguments of modern scholarship. The “charge” is that we have relied on the

revisionist scholars such as Ryckmans, Breton and Beeston against traditionalist scholars who rely on Dr. Ditlef Nielsen’s pioneering scholarship from the 1920s.

We are not told why modern scholars such as Jacques Ryckmans, Jean-François Breton and A. F. L. Beeston can be considered “revisionists” and what makes the scholarship of Ditlef Nielsen “traditional”. Regrettably, much of their argument is based on this charge rather than actually presenting historical evidences to prove their point of lunar associations of South Arabian deities. Commenting on Nielsen’s theory of astral triads, the missionaries say that:

About the only way to decisively refute the triadic theory would be if a theogonic myth was unearthed that explained the South Arabian pantheons differently, or the theory proved less than useful in explaining the data, yet there is a serious debate about only two of the gods.

The tacit assumption here, of course, is that Nielsen already had the evidence to show the proof for the existence of astral triads in the South Arabian pantheons and that any alternate account, as espoused by “revisionists”, must be supported by evidence. This argument is quite strange and is a weak attempt to reverse the burden of proof; it rather shows the ignorance of the missionaries concerning the thesis of Nielsen. Nielsen’s thesis can be summarized like this.[82] The old Arabian religion was the mother of the other Semitic religions and it was composed of the astral triad of Sun-Moon-Venus. This triad corresponded to Father-god, Mother-goddess and divine Son, respectively. Nomads worshipped the star Venus, but when they became agriculturalists they revered the sun and paid less attention to the star and the moon. The astral nature of old Arabia contrasted with that of Babylonia. Arabia, with its nomad night-journeys, chooses the moon, while the peasant life of Babylonia choose the sun. Next, a sacred moon leads sacred phases with corresponding ritual seasons. Hence a lunar reckoning of time developed in Arabia and a solar reckoning in Babylonia. After the sacred times and seasons being provisionally settled, next comes the turn of places and symbols. Anything curved or associated with a curved shaped was consigned to lunar symbolism, as it imitates the shape of a crescent moon. Thus bulls, bullheads and ibexes showing the curved horns became the symbols of the Moon-god. Among the southern Semites, sun is feminine and Venus is masculine, as is moon and this formed the trinity of Father-Moon, Mother-Sun and Son-Venus. This is the gist of Nielsen’s thesis on the origin of the Semitic religion.

To begin with, Nielsen’s very claim that the starting point of the religion of Semitic nomads was marked by the astral triad of Sun-Moon-Venus, the moon being more important for the nomads and the sun more important for settled tribes, was startling to many scholars. He painted almost the entire religion of the Middle East with the same brush of astral triads. One can see that there is nothing “traditional” about such a claim, as the knowledge about the South Arabian pantheon and, in general, the Semitic religion was still in its infancy during Nielsen’s time. Giving a chronological view of Arabian epigraphy and connecting it to the study of the religion of Semitic people, Henninger says:

Towards the end of the nineteenth century and on into the twentieth, South-Arabic and proto-Arabic epigraphy (entirely absent from the work of Wellhausen) was taken more and more into consideration. Although not particularly relevant to the study of the nomadic peoples, D. Nielsen from 1904 onwards made use of epigraphic evidence as a basis for reconstructing an astral religion common to proto-Semitic peoples and thus also attributable to Arab Bedouin. This much too speculative theory met with strong opposition….

Credit must be given to G. Ryckmans for producing an important survey in his monograph, Les Religions arabes préIslamiques, first published in 1947. He made extensive use of the expanding corpus of epigraphic material while carefully avoiding Nielsen’s dubious theories….[83]

While discussing Stephen Langdon’s Semitic mythology[84] which resembles Nielsen’s thesis, Barton says:

It is assumed, both in the treatment of Semitic and Sumerian deities, that the earliest gods were celestial – sun, moon, sky, and astral gods – an assumption, which, though followed by some recent writers such as Ditlef Nielsen, is contrary to the conclusions of sound anthropology, and was discarded for the Semitic field by W. Robertson Smith nearly half a century ago.[85]

J. Gray discussed the studies of Maria Höfner on ancient south Arabian religion. He pointed out that the increased availability of epigraphic material has resulted in correction of theories of Ditlef Nielsen as well as their refutation.

Aided by philology and by the analysis of the epigraphic symbols of the gods, she succeeds in showing that the pantheon was relatively simple and restricted, and was dominated by the first three gods above-mentioned, which were worshipped under a great number of epithets, functional and local. She is able also to correct certain former theories, such as that of Ditlef Nielson, who argued for a family relationship between Almaqa, Šams and Attar as moon, sun and Venus in the relationship of father, mother and son (Handbuch der altarabischen Altertumskunde, I, 1927). The author not only explodes this theory of a trinity, but demonstrates that the gods, though believed to be manifest in the moon, sun and Venus star, were agrarian deities, Attar being principally influential in irrigation, Almaqa in seasonal rain and Šams playing a relatively minor role. Attar was besides a war-god and protector.[86]

It is not surprising that W. Montgomery Watt pointed out:

The divergent theories of Dietlef Nielsen are not generally accepted. These recount what is known about a large number of gods and goddesses and about the ceremonies connected with their worship. As our knowledge is fragmentary and, apart from inscriptions, comes from Islamic sources, there is ample scope for conjecture. These matters are not dealt with here in any detail as it is generally agreed that the archaic pagan religion was comparatively uninfluential in Muhammad’s time.[87]

In fact over sixty years ago William F. Albright issued a general warning regarding Nielsen’s study of the South Arabian pantheon. Although Albright noted Neilsen’s contribution to the study of South Arabian pantheons, he concluded that he had “gone much too far in trying to carry it through Near-Eastern polytheism in general.”[88] Albright also pointed out Nielsen’s strong tendency to over-schematize the material and hence the latter’s work should be used with great caution.

The subject of divine triads in the ancient Near East, particularly Arabia and Syria, has been discussed repeatedly by D. Nielsen, especially in his books Die altarabische Mondreligion (1904), Der dreieinige Gott in religionshistorischer Beleuchtung (1922) and in his paper “Die altsemitische Muttergöttin“, Zeits. Deutsch. Morg. Ges., 1938, pp. 526-551. Owing to Nielsen’s strong tendency to over-schematize and to certain onesidedness in dealing with the material, his work has been only moderately successful and must be used with great caution.[89]

In other words, the reduction of the pantheon of South Arabian gods to a triad by Nielsen was not based on actual evidence but mere speculation which made his theories dubious which consequently invited incisive rejoinders from 1924 onwards, which the missionaries did not take the opportunity to check.[90] Moreover, it has been pointed out by Beeston that in order to understand the religion and culture of ancient Southern Arabia, it must be borne in mind that the monuments and inscriptions already show a highly developed civilization, whose earlier and more primitive phases we know nothing about. This civilization had links with the Mediterranean region and Mesopotamian areas – which is evidenced by the development and evolutionary trends of its architecture and numismatics. This exchange certainly influenced the religious phenomena of the culture and it is primarily here we should look to illuminate the theological outlook of the Southern Arabian region; certainly not among the nomadic bedouin of the centre and north of the Arabian peninsula. Clearly, Nielsen failed to take into account these crucial principles and it led him to construct an extravagant hypothesis that all ancient Arabian religion was a primitive religion of nomads, whose objects of worship were exclusively a triad of the Father-Moon, Mother-Sun and the Son-Venus star envisaged as their child.[91] The “traditional” and “pioneering scholarship” of Nielsen turned out to be neither of the two; it was exaggerated, speculative, dubious and consequently discarded. Even in spite of the compelling body of evidence to the contrary, the missionaries claim:

It is well known that the moon, sun and Venus were worshipped everywhere in the ancient world, and it was most natural for pagans to worship them as a triad of closely related gods.

If this is indeed true, according to Ditlef Nielsen’s “pioneering scholarship” Yahweh must be a part of some astral outfit. According to the “traditional” and “pioneering scholarship” of Nielsen, Yahweh was actually a Moon-god and a part of the triad of Yahweh – Ba‘al – ‘Aštart. He says:

The old Arabic iconless cult is also found among the Hebrews; as is the old Arabic triad of gods. In the triad Yahweh – Ba‘al – ‘Aštart, which was revered by the people during the era of the kings, Ba‘al is according to usual northern Semitic custom, the male Sun, and ‘Aštart the female Venus; but the original old Arabic form of the family of gods, where Venus is male and the Sun is the female mother-god, shows up in parallel; e.g., in the dream of Joseph (Genesis 39:9-10), in Yahweh’s wedding with the Sun and in the frequent female sex of the Šemeš (Sun).

Yahweh, the main god of the triad, is in its original nature a distinctly old Arabic god figure. The name itself probably also occurs in Lihyanite inscriptions.

In a triad where the other two gods are the nature gods, Sun and Venus, one would also expect to find the Moon, and indeed there is evidence that the Hebrew Yahweh originally was a lunar god. Of course, one cannot say that the Old Testament god who rules over nature is simply a lunar god, but many rudiments, in particular in the cult, show that it grew out of the same natural basis as the other folk gods and nature gods of the old Arabic culture.

Just as the horse was the holy animal for the old Arabs (cf. page 227) and Hebrews (2 Kings 23:11), so was the bull the animal of the lunar good (cf. page 214). It is for this reason that Yahweh was depicted and worshipped in the shape of a bull, and its altar carries »horns« (Exodus 32:4ff, 1 Kings 12:28, Hosea 8:5).

The night is always the sacred time and the time when Yahweh reveals himself. The festivals were originally moon festivals and are still tied to the lunar phases today. New moon and full moon were solemnly celebrated The waxing and waning moonlight is also reflected in the sacrifice by fire. For example, during the autumn festival (Numbers 29:12-32), 13 young bulls are sacrificed on the first day of the full moon, 12 on the second day, 11 on the third day etc., down to 7 animals on the 7th day. This week begins with the full moon and ends with the last quarter. One should note that 7 bulls are sacrificed just on the 7th day of the week, so that this scale really requires a sacrifice of 14 bulls on full moon at the 14th day of the lunar month, and that the number of bulls diminishes in parallel with the moon waning.

Already 22 years ago, the author has shown evidence that with the old Arabs and Hebrews the Sabbath or weekly holiday was tied to the lunar cycle by bi-monthly leap days during new moon. The loss of this leap mechanism can apparently be explained with the fight against the lunar cult, just as Muhammad abolished solar times for religious festivals and solar leap days in the calendar for similar motives and to finally eradicate the solar cult.

The terms used on the appearance of Yahweh are frequently the same astronomical terms as used for the appearance of the [new] moon, moon-rise, and moon-set; the whole religious symbolism is also a tell-tale sign of lunar origins.[92]

A supporting evidence of the lunar origins of the Hebraic religion also comes from the work of Lloyd Bailey. Bailey noted the similarities between Israelite deity Ēl Šadday and Amorite Bel Šadê and their lunar origins.[93] Similar conclusions were also reached by E. L. Abel who says:

… the definite allusions to the moon cult in the names of the patriarchs and their families, and the affinities between the Ugaritic El and the patriarchal god, all suggests that El Šadday, the god of patriarchs was a lunar deity and in turn that the patriarchs were followers of the lunar cult.[94]

Mention must be made of the fact that Julius Lewy suggested a number of years ago on entirely different grounds that Ēl Šadday was the Moon-god Sin.[95] Not surprisingly, Andrew Key also noted that there existed traces of worship of the Moon-god Sin among the early Israelites.[96] A few words need to be said about the bovine symbolism of Yahweh in the Old Testament, a topic which has been widely discussed in the scholarly literature, especially one of the epithets of Yahweh, the “אביר (ʾabyr) of Jacob” (Genesis 49:24).[97] This is normally translated as the “mighty God of Jacob” or the “mighty One of Jacob”. However, literally and basically the word ʾabyr in Northwest Semitic languages such as Ugaritic means “bull”. The cognate in Ugaritic, a language written in cuneiform and closely related to Hebrew, is ibr[98] and is paralleled with two words, tr[99] and rum,[100] that mean “bull” and “buffalo”, respectively.[101] The root meaning may have been “mighty” or “powerful”, however, as we have observed, it is also the name of an animal.[102] The horned bull has implications of strength (hence the translation “mighty One”), warrior skills, fertility and youth. For this reason, the “ʾabyr of Jacob” is also translated as “the Bull of Jacob”.[103] That “the Bull of Jacob” refers to Yahweh in post-Mosaic times as well is clear from passages such as Isaiah 49:26, 60:16, and Psalm 132:2, where the ʾabyr of Jacob is paralleled with Yahweh. Commenting on the bovine symbolism of Yahweh in the Hebrew Bible, Moshe Weinfeld says:

That the divine symbol of bull was associated with Bethel may be learnt from Genesis 49:24, where the term ʾabyr Jacob, ‘the bull of Jacob’, applied to the God of Israel, is coupled with ʾbn Israel, ‘the stone / rock of Israel’, in other words the massebah, of Bethel. For the bull / ram imagery in connection with God of Israel cf. Num 23:22, 24:8.

One should however be aware of the fact that applying a symbol of a bull to God of Israel does not necessarily mean that the people believed that the bull represented YHWH himself. According to some scholars… the calf was considered the pedestal upon which YHWH was enthroned and thus was in parallel in function to the “cherubim” in Jerusalem. Bull pedestals of the god Baal-Hadad are also attested in the Hittite and Syrian iconography…[104]

Along with several passages in Exodus such as 32:4, 32:8 and 32:31 in which the calf is expressly identified with the God of Israel, other passages also highlight the close symbolism of Yahweh and the calf.[105] According to the Old Testament, when Jeroboam I, the first King after the split of the united kingdom of Israel and Judah, wanted to dissuade the people of the newly established northern Israelite kingdom from going to Jerusalem to worship Yahweh there, he established two new religious centres, Dan and Bethel, and had two golden calves crafted and installed there. It would not have been possible to use the calves in these circumstances if the Israelites were not already familiar with the concept of calf worship and its acceptance as one of the symbolic animals of the God of Israel. As Aaron Rothkoff has pointed out in the Encyclopaedia Judaica,

In any case Jeroboam’s initiative must have had some basis in an old tradition; otherwise he could not have succeeded in his enterprise.[106]

The bull symbolism of Yahweh coupled with the long historical tradition of worship of the Moon-god among the Israelites is clearly in line with the “traditional” and “pioneering scholarship” of Ditlef Nielsen who had earlier established using similar evidences that Yahweh originally was a Moon-god.

It goes without saying that the missionaries’ argument contains serious flaws and contradictions. The “traditional” and “pioneering scholarship” of Ditlef Nielsen has established Yahweh’s “moonotheism”, i.e., his credentials as a Moon-god by taking into account Yahweh’s voracious appetite for bulls, his love for their horns, his bovine symbolism among other things. For the missionaries this should sound like a very familiar argument which they have used to allege the lunar associations of South Arabian deities as well as Allah. On the other hand, the missionaries have considered any deviation from Nielsen’s “traditional” and “pioneering scholarship” as “revisionism”, thus establishing that they have been worshipping the Moon-god cult of Yahweh; a devastating consequence of using “critical evaluations” of a “third-party” without proper understanding and verification. After this brief digression, let us now discuss the “amazing discoveries” that were made in Southern Arabia and what they tell us about ilāh.

WHAT DO THE “AMAZING DISCOVERIES” TELL US ABOUT ILĀH?

Morey had mentioned that some “amazing discoveries” were made in Southern Arabia by archaeologists such as G. Caton Thompson, Carleton S. Coon, Wendell Phillips, W.F. Albright, Richard Bower et al. and this has resulted in the “demonstration” that the predominant religion in Arabia was Moon-god worship. We have conclusively demonstrated that this is indeed false. Many of these archaeologists used Nielsen’s arbitrary assignment of astral significance to the deities. However, modern studies have proven that the predominant religion was solar worship in the kingdoms of Sheba and Hadramaut. The exact nature of the astral significance of the patron deities in the kingdoms of Qataban and Ma‘in is uncertain. Thus Segall’s statement that “according to most scholars, South Arabia’s stellar religion had always been dominated by the Moon-god in various variations” is incorrect and represents an example of outdated scholarship.[107] Morey also plundered Coon to support his claim that Allah was a pagan Arab “Moon-god” of pre-Islamic times. According to Morey:

As Coon pointed out, “The god Il or Ilah was originally a phase of the Moon God.”

The Moon-god was called al-ilah, i.e. the god, which was shortened to Allah in pre-Islamic times. The pagan Arabs even used Allah in the names they gave to their children. For example, both Muhammad’s father and uncle had Allah as part of their names. The fact that they were given such names by their pagan parents proves that Allah was the title for the Moon-god even in Muhammad’s day.[108]

Morey then adds:

Prof. Coon goes on to say, “Similarly, under Mohammed’s tutelage, the relatively anonymous Ilah, became Al-Ilah, The God, or Allah, the Supreme Being.”[109]

There are several problems with Morey’s quotes. Firstly, Morey clipped the sentence out of a larger paragraph. He deceptively left out a crucial part, and separated the other two parts as though they were two unrelated quotes. The actual quote from Coon reads:

The god Il or Ilah was originally a phase of the Moon God, but early in Arabian history the name became a general term for god, and it was this name that the Hebrews used prominently in their personal names, such as Emanu-el, Israel, etc., rather than the Ba’al of the northern semites proper, which was the Sun. Similarly, under Mohammed’s tutelage, the relatively anonymous Ilah became Al-Ilah, The God, or Allah, the Supreme Being.[110]

Coon’s claim that “Il or Ilah was originally a phase of the Moon God” comes from the claim that the patron deities of ancient South Arabia such as Wadd, ‘Amm, Sayīn and Ilmaqah were all Moon-gods.[111] A claim similar to that of Coon which says Allah was “originally applied to the moon” can also be seen in Everyman’s Dictionary Of Non-Classical Mythology. Concerning “Allah” it says:

Allah. Islamic name for God. Is derived from Semitic El, and originally applied to the moon; he seems to have been preceded by Ilmaqah, the moon god.[112]

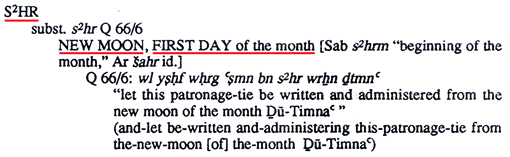

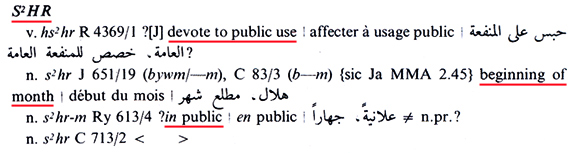

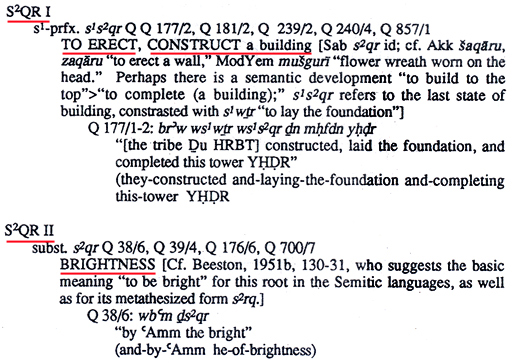

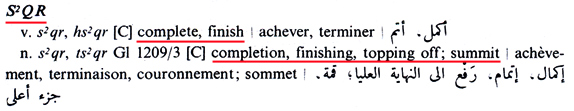

This takes us to the second point. The dictionaries of Qatabanian and Sabaean dialects compiled from the “amazing discoveries” of the inscriptions in Southern Arabia do not support Coon’s view that il or ilāh was “originally a phase of the Moon god” nor gives credence to the allegation that Allah was “originally applied to the moon”. As to what exactly il and ilāh mean in epigraphic South Arabian (i.e., Qatabanian and Sabaean inscriptions) as well as how they are related to their cognates in Arabic and Hebrew is depicted in Figure 6.

(a)

(b)

(c)

Figure 6: Discussion on ‘IL and ‘ILH in (a, b) Qatabanian[113] and (c) Sabaic dictionaries.[114] Note that the lexicons also mention that ilh in the Qatabanian and Sabaean dialects is similar to Arabic ilāh and Hebrew elōah.

Similar views are also expressed by D. B. Macdonald in the Encyclopaedia of Islam. He says that ilāh simply means deity. Concerning ilāh he says:

… for the Christians and (so far the poetry ascribed to them is authentic) the monotheists, al-ilāh evidently means God; for the poets it means merely “the one who is worshipped”, so al-ilāh indicates: “the god already mentioned”… By frequency of usage, al-ilāh was contracted to Allāh, frequently attested in pre-Islamic poetry (where his name cannot in every case have been substituted for another), and then became a proper name (ism ‘alam)…

ilāh is certainly identical with elōah and represents an expanded form of an element –l– (il, el) common to the semitic languages.[115]

From the discussion, it is clear that in Qatabanian and Sabaean il or ilāh was neither “originally a phase of the Moon god” nor “originally applied to the moon”. It simply means god/God. Furthermore, ilh in the Qatabanian and Sabaean dialects is similar to the Arabic ilāh and the Hebrew elōah. Moreover, the allegations that il or ilāh was “originally a phase of the Moon god” or that Allah was “originally applied to the moon” stems from the view of the earlier archaeologists and scholars that Moon-worship was predominant in Southern Arabia. This claim has been shown as erroneous and unsupported by any evidence. In fact, the evidence points to a predominance of Sun-worship in Southern Arabia.

Thirdly, Morey’s approach left out of Coon’s statement what would disprove his most important argument against the God of Islam. Morey is adept at repeating that Allah is not the God of the Bible but the Moon-god of pre-Islamic Arabia. It would have been inconvenient for him to repeat what Coon had said that “it was this name that the Hebrews used prominently in their personal names, such as Emanu-el, Isra-el, etc.” Going by Morey’s “logic” the Hebrew name Emanu-el which Morey considers a name for Jesus would now mean that “Moon-god is with us”.

Fourthly, al-ilāh is not the same as il or ilāh. The words are spelt very differently. Coon says that “Ilah became Al-Ilah” in Muhammad’s teachings. Obviously, then, al-ilāh was not the Moon-god according to Coon but only according to Morey.

Now that the case for finding the Moon-god in the “amazing discoveries” of Southern Arabia has come to a naught, let us now turn our attention to Northern Arabia.

4. A Wild Goose Chase In Northern Arabia

For his evidence of a Moon-god cult in Northern Arabia, Morey starts of by saying:

Thousands of inscriptions from walls and rocks in Northern Arabia have also been collected. Reliefs and votive bowls used in worship of the “daughters of Allah” have also been discovered. The three daughters, al-Lat, al-Uzza and Manat are sometimes depicted together with Allah the Moon-god represented by a crescent moon above them.[116]

For Southern Arabia Morey told us about alleged Moon-god worship everywhere and he furnished us with names of discoverers, dates of discoveries, names of discovery sites, and lots of pictures to boot. Why is it that when it comes to Northern Arabia he offered not a shred of evidence? The only authorities he quotes to support his statement that the “three daughters, al-Lat, al-Uzza and Manat are sometimes depicted together with Allah the Moon-god represented by a crescent moon above them”, are Isaac Rabinowitz,[117] Edward Lipinski[118] and H. J. W. Drijvers.[119]

To begin with, none of these scholars even mention that Allah was a Moon-god in their works. Rabinowitz’s two papers in the Journal Of Near Eastern Studies deal with mention of Han-‘Ilat on vessels from Egypt. The pagan goddess Atirat, who was widely worshipped in the Middle East, was discussed by Lipinski. There is no mention of al-‘Uzza and Manat in his paper, let alone they being the daughters of “Moon-god” Allah. As for the work of Drijvers, he discusses extensively the iconography of Allat in Palmyra. If there was something significant in these writings, Morey would have made direct quotation. The fact is that none of these works mention Allah was a Moon-god. Once again, Morey shows himself adept at fabricating evidence.

The standard of a work can be determined by how accurately the source material is cited. Morey’s book The Islamic Invasion: Confronting The World’s Fastest-Growing Religion can be rated as one of the top-class howlers when it comes to accuracy.[120] Let us take a look at some of the samples.

Morey claims that “Newman concludes his study of the early Christian-Muslim debates by stating”:

“Islam proved itself to be…a separate and antagonistic religion which had sprung up from idolatry”.[121]

The actual quote on the other hand reads:

The first three centuries of the Christian-Muslim dialogue to a great degree molded the form of the relationship which was to prevail between the two faiths afterward. During this period, Islam proved itself to be less a wayward sect of the “Hagarenes,” from a Christian perspective, and more a separate and antagonistic religion which had sprung up from idolatry.[122]

It was not Islam that proved itself to be a separate and antagonistic religion which had sprung up from idolatry; rather it was all from a Christian perspective! Morey conveniently left out the passage highlighted above to show that Islam proved itself to be a separate and antagonistic religion which had sprung up from idolatry.

Right after mentioning Newman’s quote, Morey goes on to say that Caesar Farah also concluded:

“There is no reason, therefore, to accept the idea that Allah passed to the Muslims from the Christians and Jews.” The Arabs worshipped the Moon-god as a supreme deity. But this was not biblical monotheism.[123]

Farah, on the other hand, actually states:

Allah, the paramount deity of pagan Arabia, was the target of worship in varying degrees of intensity from the southernmost tip of Arabia to the Mediterranean. To the Babylonians he was “Il” (god); to the Canaanites, and later the Israelites, he was “El‘; the South Arabians worshipped him as “Ilah,” and the Bedouins as “al-Ilah” (the deity). With Muhammad he becomes Allah, God of the Worlds, of all believers, the one and only who admits no associates or consorts in the worship of Him. Judaic and Christian concepts of God abetted the transformation of Allah from a pagan deity to the God of all monotheists. There is no reason, therefore, to accept the idea that “Allah” passed to the Muslims from Christians and Jews.[124]

The problem with Morey’s quote is that he so separated the last sentence from the rest of the paragraph, that he made it say something different from what it used to say in the context of that paragraph. That passage was saying that the God who was called Ilah in South Arabia was called El by the Israelites. This fact would have ruined Morey’s entire Moon-god theory, so Morey conveniently concealed it. Moreover, Farah never said that the Arab worshipped the Moon-god as a supreme deity!

Let us now move to Chapter IV (“The Cult Of The Moon God”) of Morey’s book.

Arthur Jeffery’s Islam: Muhammad And His Religion is quoted to introduce the name Allah. Morey says:

The name Allah, as the Qur’an itself is witness, was well known in pre-Islamic Arabia. Indeed, both it and its feminine form, Allat, are found not infrequently among the theophoric names in inscriptions from North Africa.[125]

The actual quotation is:

The name Allah, as the Qur’an itself is witness, was well known in pre-Islamic Arabia. Indeed, both it and its feminine form, Allat, are found not infrequently among the theophoric names in inscriptions from North Arabia.[126]

Morey transforms “North Arabia” to “North Africa”, thus increasing the geographical distribution of the name Allah and Allat among the theophoric inscriptions by several fold – conveniently for Morey, a not so insignificant misquotation.

As for Alfred Guillaume, Morey says that he has pointed out that “the moon god was called by various names, one of which was Allah”.[127] Guillaume, on the other hand, writes:

The oldest name for God used in the Semitic word consists of but two letters, the consonant ‘l’ preceded by a smooth breathing, which was pronounced as ‘Il’ in ancient Babylonia, ‘El’ in ancient Israel. The relation of this name, which in Babylonia and Assyria became a generic term simply meaning ‘god’, to the Arabian Ilāh familiar to us in the form Allāh, which is compounded of al, the definite article, and Ilāh by eliding the vowel ‘i’, is not clear. Some scholars trace the name of the South Arabian Ilāh, a title of the Moon god, but this is a matter of antiquarian interest. In Arabia Allāh was known from Jewish and Christian sources as the one god, and there can be no doubt whatever that he was known to pagan Arabs of Mecca as the supreme being. Were this not so, the Qur’an would have been unintelligible to the Meccans; moreover it is clear from Nabataean and other inscriptions that Allāh means ‘the god’.[128]

It is clear that Guillaume did not say that “the moon-god was called by various names, one of which was Allah”. He only said that some scholars “trace the name of the South Arabian Ilāh, a title of the Moon god…” We have already seen from the Qatabanian and Sabaean lexicons that Ilāh simply means “god” without any astral connotations.

Many howlers can also be seen in Morey’s A Reply To Shabbir Ally’s Attack On Dr. Robert Morey: An Analysis Of Shabbir Ally’s False Accusation And Unscholarly Research. In this booklet Morey accuses Shabbir Ally of “unscholarly research”. How does Morey fare when it comes to “scholarly research”? Let us examine his scholarly credentials by taking just three examples from his booklet. Quoting the book Studies On Islam, Morey says:

“According to D. Nielsen, the starting point of the religion of the Semitic nomads was marked by the astral triad, Sun-Moon-Venus, the moon being more important for the nomads and the sun more important for the settled tribes.” Studies on Islam, trans., ed. Merlin L. Swartz, (New York, Oxford, 1981), page 7.[129]

This quote comes from Joseph Henninger’s article “Pre-Islamic Bedouin Religion” in this book. What is interesting to note is that Ditlef Nielsen’s views on the origins of the Semitic religion are no longer considered valid by modern scholars. As we have noted earlier, Nielsen’s triadic hypothesis was handed a devastating refutation by many scholars. Not surprisingly, Henninger describes Neilsen’s theories as “dubious” and “too speculative” which “met with strong opposition”.[130] In other words, the reference which Morey used to bolster his case for Allah being a Moon-god refutes the same contention!

While discussing the ibex and its religious significance in ancient South Arabian religion, Morey mentioned Wendell Phillips’ Qataban And Sheba: Exploring Ancient Kingdoms On The Biblical Spice Routes Of Arabia which allegedly says:

“The ibex (wa’al) still inhabits South Arabia and in Sabean times represented the moon god. Dr. Albert Jamme believes it was of religious significance to the ancient Sabeans that the curved ibex horn held sideways resembled the first quarter of the moon.” Qataban and Sheba: Exploring the Ancient Kingdoms on the Biblical Spice Routes of Arabia, Wendell Phillips, (New York, 1955), page 64.[131]

This quote is nowhere to be seen on that page! Checking the index of the book reveals that the only mention of ibex occurs in p. 69 where the text says:

The ibex was an animal of special veneration among the ancient peoples of Arabia, and frequently adorned sacrificial tables of offerings to the gods, such as the one we found.[132]

Another quote from this book, according to Morey, says:

“The first pre-Islamic inscription discovered in Dhofar Province, Oman, this bronze plaque, deciphered by Dr. Albert Jamme, dates from about the second century A.D. and gives the name of the Hadramaut moon god Sin and the name Sumhuram, a long-lost city… The moon was the chief deity of all the early South Arabian kingdoms – particularly fitting in that region where the soft light of the moon brought the rest and cool winds of night as a relief from the blinding sun and scorching heat of day.

In contrast to most of the old religions with which we are familiar, the moon god is male, while the sun god is his consort, a female. The third god of importance is their child, the male morning star, which we know as the planet Venus…

The spice route riches brought them a standard of luxurious living inconceivable to the poverty-stricken South Arabian Bedouins of today. Like nearly all Semitic peoples they worshipped the moon, the sun, and the morning star. The chief god, the moon, was a male deity symbolized by the bull, and we found many carved bulls’ heads, with drains for the blood of sacrificed animals.” Qataban and Sheba: Exploring the Ancient Kingdoms on the Biblical Spice Routes of Arabia, ibid. page 227.[133]

Not surprisingly, the above quote is not be found on page 227 either! A closer examination of the material reveals that this lengthy quote in Morey’s booklet comes from different pages, viz., pages 306, 69 and 64.

Dr. Jamme had deciphered a newly uncovered bronze inscription mentioning the name of the Hadhramaut moon god Sin and giving for the first time the name SMHRM (Sumhuram), a long-lost city.[134]

The moon was the chief deity of all the early South Arabian kingdoms – particularly fitting in that region where the soft light of the moon brought the rest and cool winds of the night as a relief from the blinding sun and scorching heat of day. In contrast to most of the old religions with which we are familiar, the Moon God is male, while the Sun God is his consort, a female. The third god of importance is their child, the male morning star, which we know as the planet Venus.[135]

The spice route riches brought them a standard of luxurious living inconceivable to the poverty-stricken South Arabian Bedouins of today. Like nearly all the Semitic peoples, they worshipped the moon, the sun, and the morning star. The chief god, the moon, was a male deity symbolized by the bull, and we found many carved bull’s heads, with drains for the blood of sacrificed animals.[136]

It turns out that Morey mixed up three different quotes from three different pages and ultimately transformed them into a single quote allegedly originating from p. 227 of the book Qataban And Sheba: Exploring Ancient Kingdoms On The Biblical Spice Routes Of Arabia. As for who is involved in “unscholarly research” is quite clear.

These examples from Morey’s books are enough to shred whatever remains of his scholarly credentials. A diligent researcher would be able to find more such misquotes in his books.

6. From Missionary Injudiciousness To Enlightenment?

In spite of no evidence in either the past or present scholarship that Allah was a “Moon-god” of pre-Islamic Arabia, it has not discouraged other Christian missionaries to loose hope; they have adopted what they term as a “take a scholarly “wait and see” approach”. They had over 10 years to look into the evidences presented by Morey that allegedly claimed that Allah was a “Moon-god” and yet no missionary ever came with a serious refutation from the point of view of archaeology. In the last 10 years, however, the missionary websites promoting Morey’s “Moon-god” hypothesis have increased dramatically. In order to minimize the impact of this hypothesis, the missionaries have claimed that the issue of Allah being a Moon-god does not even figure out as a “major argument” in the Christian community. They say:

It is certainly true that Muslims have been particularly annoyed about this theory, but it is definitely wrong that this was a favorite or major argument in the Christian community, let alone among Christian missionaries. Among the perhaps 200 Christian books published about Islam in the last 15 years, I would be hard pressed to name more than five authors who seriously promote that theory.

Perhaps the missionaries have forgotten that the knowledge-base in our world these days also exists in the form of zeros and ones. A quick search on Google for “Allah Moon God” throws up more than a million websites! A quick sampling would reveal that the majority of these websites belong to Christians. It can be confirmed that the huge popularity of Allah being a Moon-god has alarmed those missionaries who are involved with and are experienced in field work with Muslims, and compelled them to write an article addressing this issue. Rick Brown in an article entitled “Who Is “Allah”?” in the International Journal Of Frontier Missions – a well-known missiology journal – which appeared in the summer of 2006, addressed the issue of various claims concerning Allah by his fellow Christian brethren. He starts by saying in the beginning of his article:

Much of the anger expressed in the West has taken the form of demonizing the Islamic religion, to the extent of accusing Muslims of worshipping a demon. A key element of this attack has been the claim of some that the name Allah refers to a demon or at least a pagan deity, notably the so-called “moon god.” Such claims have even been made by scholars who are reputable in their own fields but who are poorly acquainted with the Arabic language and Middle-Eastern history. The Kingdom of God, however, is never advanced by being untruthful, so this matter bears further investigation.[137]

Contrary to the claim of the Christian missionaries, Brown admits that a “key element” of the Christian attack on Muslims is referring to Allah by calling him a “Moon god”. He also categorically states that this claim is patently “untruthful”. Not surprisingly, given the importance of the claim of Allah being a Moon-god, this is the first issue which he deals with in his article citing scholarly sources. He says:

Moon God?