The three British men who embraced Islam

The three British men who embraced Islam

There is a little-known story of three English gentlemen who embraced Islam at a time when to be a Muslim was to be seen to be a traitor to your country. Through personal journeys of still surviving relatives, the programme looks at their achievements and how their legacy lives on today.

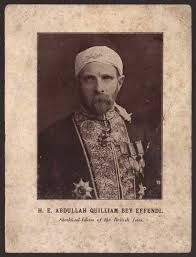

William Henry Quilliam, a local Liverpool solicitor and resident embraced Islam in 1887 (aged 31), after returning from a visit to Morocco, and took on the name Abdullah. He claimed that he was the first native Englishman to embrace Islam. His conversion led to a remarkable story of the growth of Islam in Victorian Britain. This history is now beginning to emerge and has important lessons for Muslims in Britain and around the world.

After embracing Islam, Quilliam began a campaign of Dawah, which in the circumstances of Victorian England, has to be described as the most effective in the UK to date. He became an Alim, an Imam and the most passionate advocate of Islam in the Western world. In 1894 Sultan Abdul Hamid ll, the last Ottoman Caliph, appointed him Sheikh-ul-Islam of the British Isles. The Emir of Afghanistan recognised him as the Sheikh of Muslims in Britain. He was also appointed as the Persian Vice Counsel to Liverpool by the Shah. He became a prominent spokesman for Islam in the media and was recognised by Muslims around the world. He is the only Muslim in Britain to have officially held the position of Sheikh Ul Islam of Britain. He issued many Fatwas in his capacity as appointed Leader of Muslims in Britain. These fatwas are relevant even today.

He established the Mosque and Liverpool Muslim Institute at No. 8 Brougham Terrace and later purchased the remainder of the terrace, and opened a boarding school for boys and a day school for girls. He also opened an orphanage (Medina House) for non-Muslim children whose parents could not look after them, and agreed to for them to be raised in the values of Islam. In addition, the Institute operated educational classes covering a wide range of subjects that were attended by both Muslims and non-Muslims, and included a museum and science laboratory.

In 1893 the Institute published a weekly magazine, named ‘The Crescent’, and later added the monthly ‘Islamic World’, which was printed on the Institute’s own press and distributed to over 20 countries. The Crescent was published every week and was effectively a dairy and record of Islam in Britain and the around the world. There are hundreds of archive copies of these magazines in the British Library. Without this unique weekly record we would not know of the existence of this native Muslim community of around 200 people in Liverpool, and many other parts of Britain. These offer the first attempt at Muslim journalism in the UK and offer a unique insight into a British Muslims view of events and issues in Liverpool, the UK and the Muslim world, at a crucial period of Muslims living under colonial rule.

He also wrote and published a number of books. In particular his ‘Faith of Islam’ had three editions translated into thirteen different languages, and was so popular that Queen Victoria ordered a copy and then re-ordered copies for her grandchildren. The Institute grew, and at the turn of the century held a membership of 200 predominantly English Muslim men, women and children from across the local community. Quilliam’s dawah led to around 600 people in the UK embracing Islam, many of them very educated and prominent individuals in British Society, as well as ordinary men and women. His efforts also led to the first Japanese man embracing Islam.

Quilliam eventually had to leave England after facing hostility and persecution, the first Muslim experience of ‘Islamophobia’ in the UK. He eventually returned to the UK and adopted the name Haroun Mustapha Leon, and passed away in 1932 near Woking, and was buried in Brookfield Cemetery where Abdullah Yusuf Ali, Marmaduke Pickthall and Lord Headly are also buried.

Rowland Allanson-Winn, 5th Baron Headley

The pride of place among Woking’s converts goes to Lord Headley, the 5th Baron of Headley (1855–1935), whose grave is situated in Brookwood. He announced his conversion to Islam at the hand of Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din in 1913. In those days, conversion to Islam meant incurring the wrath and displeasure of family, friends and society, and in the case of those belonging to the higher levels of society, like Lord Headley, it meant losing the respect and reputation in which you were held. Not caring for any such worldly loss, Lord Headley boldly and openly proclaimed himself a Muslim and served the cause of Islam till his death in 1935. He toured Muslim communities in several countries in the company of his teacher Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din, thus visiting South Africa in 1926, touring India in 1927, and performing the hajj in 1923.

He wrote several small booklets about Islam and many articles in the monthly Islamic Review, the journal of the Woking Mission. He worked hard on plans (which were never fulfilled) to build a grand mosque in London itself. Land was obtained in West Kensington (close to the famous Olympia exhibition centre), and in July 1937 even the foundation stone was laid by the heir to the Nizam of Hyderabad.

As a member of the aristocracy, Lord Headley mixed with the nobility and royalty of England. He lost no opportunity to explain Islam in those circles. At one after-dinner speech, attended by various august persons, he spoke on the life of the Holy Prophet Muhammad.

Muhammad Marmaduke Pickthal

Marmaduke William Pickthall was born in Cambridge Terrace, London on 7 April 1875. The elder of two sons of the Reverend Charles Grayson Pickthall (1822–1881) and his second wife, Mary Hale, Charles was an Anglican clergyman in a village near Woodbridge, Suffolk.

The Pickthalls traced their ancestry to a knight of William the Conqueror, Sir Roger de Poictu, from whom their surname derives. Pickthall spent the first few years of his life in the countryside, living with several older half-siblings and a younger brother in his father’s rectory in rural Suffolk. He was a sickly child. When about six months old, he fell very ill of measles complicated by bronchitis. On the death of his father in 1881, the family moved to London. He attended Harrow School but left after six terms.

Pickthall travelled across many Eastern countries, gaining a reputation as a Middle Eastern scholar. Before declaring his faith as a Muslim, Pickthall was a strong ally of the Ottoman Empire. He studied the Orient, and published articles and novels on the subject. While in the service of the Nizam of Hyderabad, Pickthall published his English translation of the Quran with the title ‘The Meaning of the Glorious Koran’. The translation was authorized by the Al-Azhar University and the Times Literary Supplement praised his efforts by writing “noted translator of the glorious Quran into English language, a great literary achievement.”

When a propaganda campaign was launched in the United Kingdom in 1915 over the massacres of Armenians, Pickthall rose to challenge it and argued that the blame could not be placed on the Turkish government entirely. At a time when Muslims in London had been co-opted by the Foreign Office to provide propaganda services in support of Britain’s war against Turkey, Pickthall’s stand was considered courageous given the wartime climate. When British Muslims were asked to decide whether they were loyal to the Allies (Britain and France) or the Central Powers (Germany and Turkey), Pickthall said he was ready to be a combatant for his country so long as he did not have to fight the Turks. He was conscripted in the last months of the war and became corporal in charge of an influenza isolation hospital.

In 1920 he went to India with his wife to serve as editor of the Bombay Chronicle, returning to England only in 1935, a year before his death at St Ives, Cornwall. It was in India that he completed his famous translation, ‘The Meaning of the Glorious Koran’.

Pickthall was buried in the Muslim cemetery at Brookwood in Surrey, England, where Abdullah Yusuf Ali was later buried.

رابط الموضوع: http://www.alukah.net/translations/0/88269/#ixzz3eLKguan2

Number of View :1513